The EU Copyright Directive permits Member States a neatly-worded copyright exception for “parody caricature and pastiche”. Ireland has not as yet embraced this opportunity, but as the Report of the Irish Copyright Review Committee has recommended that we do, and as the exception has recently been adopted in the UK, it can be expected to arrive on our shores soon . Over and above the fact that is an interesting question, this gives some relevance to the question “what is a parody?”

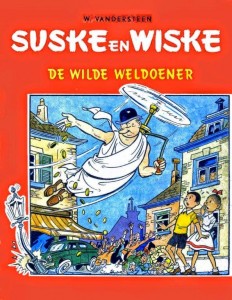

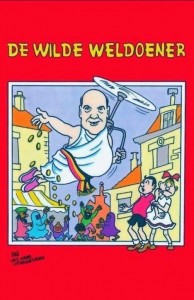

The CJEU addressed the question in a judgment (Case C-2013/13, Deckmyn) handed down on 3rd September. The case involved the use of a cartoon on the cover of a publication, Suske en Wiske (in English, Spike and Suzy) titled The Compulsive Benefactor. It is shown on the left below. The copy is shown on the right. It is a piece of political commentary on the activities of the Mayor of Ghent. In both images the events are being observed with some dismay by Spike & Suzy.

Belgian law has the parody exception, but when the case came before the hof van beroep de Brussel, that court found itself exercised about whether or not a parody needs to be funny or to mock, and whether other conditions have to be satisfied. So it sent a note up to the CJEU. Spike & Suzy went along to hear what the judges had to say.

The CJEU cleared its throat: “It is clear … that the concept of ‘parody’, which appears in a directive that does not contain any reference to national laws, must be regarded as an autonomous concept of EU law and interpreted uniformly throughout the European Union”.

Mmmmm. Spike wondered if this meant that – if it has to be funny – it has to be funny not just in Brussels, but in Barcelona and Bratislava too?

Warming a little to the task, the Court addressed the questions of the Belgian court. It said the essential characteristics of parody are the following:

• it evokes an existing work, while being noticeably different from it

• it constitutes an expression of humour or mockery

It need not, the Court said, do any of the following:

• display an original character of its own

• relate to the original work itself

• be obviously by a different author to that of the source work

• mention the source work

Suzy was wondering how many other things she and Spike could be used to parody and would it not be better if a parody had to have some relationship to the original. She began to redden with anger at the idea that she and Spike might be used for, well, almost anything.

The Court moved on briskly however, adding that “the interpretation of parody must, in any event enable the effectiveness of the exception …to be safeguarded and its purpose to be observed…..The objectives of the directive …include…a harmonisation which will help to implement the four freedoms of the internal market and which relates to observance of the fundamental principles of law and especially of property, including intellectual property, and freedom of expression and the public interest”

At this point Spike & Suzi felt a bit overwhelmed. …the four freedoms of the internal market…the fundamental principles of law….they wondered if they needed to stay until the end. However the Court was nearly finished. “In addition… the application, in a particular case of the exception for parody …must strike a “fair balance” between the rights and interest of authors on the one hand and the rights of users of protected subject-matter on the other”. For that, all of the circumstances of the case must be taken into account. And that is a matter for the national court.

And the judges gathered up their papers and went home.

On the way back on the train, Spike and Suzy agreed that they might have preferred a bit more. Or even a bit less. Maybe something like the decision of the American judge in the case of Nike Inc. v. “Just Did It” Enterprises, who said a parody is “a take-off, not a rip-off.”